The Stonewall Riots. The Nights That Changed The World

Stonewall. A word that has become burned into the consciousness of every person in the queer and trans community. An event so massive that it completely changed the course of queer rights.

But more than 50 years after the event, for many The Stonewall Riots has become just a name they’ve heard over and over. And they know little about what really happened, and why it was so earth shattering. The exact events of those nights are blurred, perhaps inevitably given the confusion, passion and mayhem of something so spontaneous and chaotic. Many of the people who were there are no longer with us, and many others didn't realise how huge an impact it would have. Also much of the history has slipped into mythology rather than fact.

So it’s worth looking at the background to the riots, what actually went down on that hot June night in 1969 and examining the effect of arguably the most important moment in the history of the gay rights movement.

Gay Rights In The 1960s

It’s important to understand how appalling rights for gay and transgender people were in the ‘60s. While the counterculture movement was thriving in the US, the queer civil rights movement was still nascent. In every state bar one homosexuality was still a criminal offence.

Gay men and women were regularly targeted by police, subjected to harassment and persecution, and beatings were commonplace. Many police forces were encouraged to treat queer and trans people with brutality. Not only that, but groups of vigilantes prowled the streets of many cities searching for gay men, beating any they found. Sometimes the beatings became murders.

“We all had friends who were beaten, maimed, thrown out of their house, informed on by the cops, tragic stories. But there was nothing you could do about it.”

Most people in the queer or trans community were forced into secrecy and into gay ghettos, where they lived in a subculture, rejected by society. In New York there were laws preventing gay men and women being served alcohol in public to stop them gathering.

In many places bartenders even refused to serve people they suspected of being gay. A few bars existed that were unofficially queer hangouts, but they were raided almost weekly and names and addresses were taken.

It’s worth bearing in mind that transgender wasn’t a recognised identity at the time and many trans people described themselves as drag queens or transvestites. Which is why some trans hostile people now claim that trans people were not present at Stonewall.

The main gay rights organisations were the Mattachine Society, for gay men, and Daughters Of Bilitis, for lesbians. And while they did have some success with changing oppressive laws, such as the 1966 ‘Sip-in’, in which Mattachine members turned up en masse at NYC straight bars and then sued them if they were turned away. They were largely advocating for integration into heteronormative society rather than gay liberation.

There seems little hope that LGBTQ+ people would escape from the cycle of violence they’d been subjected to for so long.

The Stonewall Inn

There were a few places where there was greater tolerance of gay men and women. Small sections of New Orleans, San Francisco and New York in particular. And it was in one of those areas, Greenwich Village, that on 18 March 1967 The Stonewall Inn opened, on Christopher Street between West 4th and Waverly Place.

We say it opened, but actually it was ‘reopened’ following a fire. Before it had just been a restaurant and bar, when it reopened it had been painted black inside and was now unofficially catering exclusively to the local gay community.

It soon became an institution. While it was one of several gay bars in the Village it stood out from the rest because it was the biggest gay venue in the US, and it had low prices ($1 on weeknights and $3 at the weekend).

Also, it was the only gay bar in the city that allowed queer people to dance with others of the same gender, which was a massive draw.

However, perhaps the most significant reason why events of that night became so explosive was because The Stonewall welcomed everyone, whereas many other venues barred drag queens, trans people, effeminate men, who were known as the “flamers”, and the street kids, of which there were many in NYC.

These street kids were usually young men who’d come to Greenwich Village to escape oppression elsewhere and who had nowhere to live. The Stonewall Inn gave them a place to go and the chance to meet someone they could go home with. These kids had nowhere else to go. The Stonewall Inn was literally their place. So the clientele was significantly edgier than in any other venue.

As with all the gay bars in Manhattan, it was run by the mafia. The place was unlicensed, there were no fire escapes, the drinks were watered down and the floor was usually wet because of the overflowing toilets. And some gay men in New York had a pretty dim view of it.

Jim Fouratt, who was around at the time described it as a dive, awful and sleazy in an interview he did with Martin Duberman for his book on Stonewall.

But for those who went to the Stonewall it was their place, and they loved it.

The Build Up To The Riots

The fact that the bar was unlicensed and illegal meant that the owners needed to bribe the police in order to remain open. And hefty bribes, estimated at $1,200 a month were paid. However, the police still needed to make sure they were seen to be discouraging illegal activity.

Consequently the Stonewall Inn was raided at least once every month usually every week. But usually early in the evening when it was quieter to allow for the bar to run a full evening. Each time a few patrons were arrested.

In the months leading up to June police became less tolerant of the gay nightlife. Drugs were starting to be sold and taken at venues and resentful of the mafia owners. Several bars were closed down and raids became more regular.

Police did usually forewarn management of raids so they could be away, but for the regulars their only warning was when the door security pressed a secret button and the lights went up. What followed was traumatic for the uninitiated, but had become mundane for the regulars.

In the wider world there was a groundswell of anger amongst youth who were beginning to feel that peaceful change was never going to happen. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy two years before, plus the putting down of the student riots in France and the brutal response to uprisings by young people both in the US and around the world was having an effect.

A feeling of disenfranchisement took hold and people were feeling they had nothing to lose. And a series of violent homophobic attacks had put the whole community on edge.

How The Stonewall Riots Started

On the evening of the 27th June the regulars would have been relaxed. The Inn had already been raided three days previously so another would be extremely unlikely, also it was past midnight, and usually raids happened earlier to allow the venue to settle down and have a normal night afterwards. But that night Police deputy Inspector Seymour Pine and his men from the 6th Precinct were determined to find enough to close the place down for good.

As usual, undercover officers went in to gather evidence of liquor and drugs being sold and of ‘people dressed as members of the opposite sex’ who were a particular target for arrest. There was a criminal statute that allowed for the arrest of anyone not wearing at least three articles of gender-appropriate clothing. Pine said later that these people were usually no trouble, but when the main raid began at 1.20 a.m. they put up more resistance than usual. And as a result Pine decided to arrest more people.

But for once, those who were released decided to hang around outside rather than disappear and be thankful to have escaped. The mood was playful at first and as more were released they joined the growing throng.

But there was also an undercurrent of resentment. With people wondering why they should have to put up with this. And as police began to push those who were being arrested into the waiting vans the mood changed.

Boos and jeers started to ring out. Several shouts of “police brutality” came from the crowd and as tensions rose Craig Rodwell, a local gay activist and former boyfriend of Harvey Milk who had happened to be passing shouted ‘Gay Power’, and others took up the chant.

When a drag queen was beaten to the floor by a police baton and butch lesbian Stormé DeLarverie began a five minute tussle with four officers who were trying to force her into a squad car the anger in the crowd increased. The spark that ignited the explosion was DeLarverie, who finally escaped the clutches of the police and screamed’ “Why don’t you guys do something?”

People immediately started throwing coins at the police, drag queens fought with officers to grab the keys to their handcuffs and scuffles erupted as for the first time ever, the queer kids refused to put up with the treatment they were given and fought back. In the mayhem the three full police vans attempted to leave but were prevented by the crowd, who started to rock them to turn them over. And a riot ensued. Cars were upended, tyres were slashed.

And then someone threw a cobblestone at the police.

It’s not clear who threw that first brick. Some, said it was Marsha P. Johnson, but she stated later that she wasn’t there at this point. Others suggested it was Zazu Nova, a local sex worker and trans woman. There are several different candidates cited in the statements from those who were there. But it had a chilling effect. Police retreated back into the Inn and barricaded themselves in.

But this ignited even greater anger, as the crowd became determined to reclaim the place they felt was their home. Flaming rags soaked in lighter fluid were thrown through windows and soon flames were coming out of the Inn, as the police fought to put out the fires.

The crowd outside grew larger as participants called friends to come down to take part in this incredible uprising against the police and the numbers reached about 600. But the police also called in reinforcements, and soon several vans of riot officers arrived.

From that point the night turned into a pitched battle between the two groups that lasted for hours, with protesters taunting riot police, and the ‘flamers’ dancing in a kickline and singing provocatively in front of them. Protesters later remembered it as a night of unparalleled joy. Things only petered out when exhausted protesters went home to sleep.

On Saturday 28th June, thanks to Rodwell’s frantic phone calls, the New York papers all ran stories of the events of the early morning. And as a result crowds again began to assemble in Christopher Street, reaching more than 2000. Even some of the straight bars in the area opened their doors to help.

The unrest again turned angry as buses and cars were surrounded, Marsha P. Johnson smashed a police car windscreen and coins were thrown at police. There were more arrests, more pitched battles and more dancing. But by 4am on the Sunday morning most people had dispersed. There were some more clashes with police over the following four nights but nothing on the scale of the first two.

And then the uprising was over.

The Immediate After Effects of Stonewall

The feeling within the gay, lesbian and trans community was one of incredible energy in the weeks after the riots. But despite that, most people, even those who had taken part, didn't think it would amount to anything. Many others however, were given a new direction and felt that this was a turning point, that they’d ‘had enough of oppression’ and there was no going back.

Several activists knew they couldn’t afford to lose the momentum they’d built and the Gay Liberation Front, and later the Gay Activists Alliance, were born to take direct action to demand gay rights and equality in a much more direct and forceful way than the Mattachine Society or Daughters Of Bilitis had.

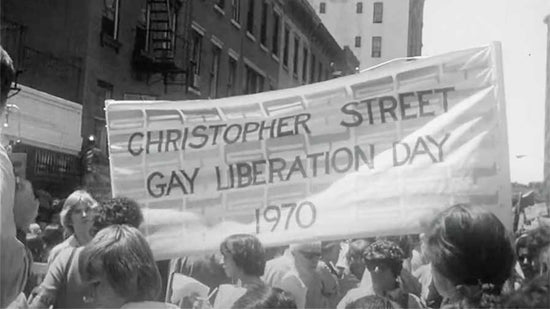

In the month that followed Martha Shelly, a lesbian who had been a co-founder of the GLF, and later went on to form The Lavender Menace, had the idea of an event to commemorate the riots. The result was the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day, held in New York on the last weekend of June.

And so, on Sunday 28th June 1970 what was effectively the first pride event was held. On the day before, a demonstration was also held in Los Angeles and marches were held in San Francisco and Chicago.

Later in 1970 Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera formed Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaires (STAR) to help people on the fringes of the LGBTQ community such as gender non-conforming people and sex workers. That started as a trailer and soon became an apartment for those in need.

In 1971 the movement spread to many other US cities and to Europe, with pride marches in London, Paris, Berlin and Stockholm.

See Our Protest T-Shirts

The Legacy Of Stonewall

The most immediate effect of the riots was the creation of the GLF and GAA groups that helped to shape the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement and laid the groundwork for the fight for equality that continues today.

But the Stonewall uprising also sparked a much broader cultural shift. Prior to the riots, homosexuality was seen as taboo and something to be ashamed of. After the riots, queer people began to demand visibility and representation in mainstream culture. This led to the emergence of queer literature, music, film, and art, which helped to create a sense of community and pride among LGBTQ+ people.

One thing is for sure, the legacy of the riots owes a lot to Craig Rodwell and the group that used the momentum it gave them to create the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day march. Had that not been a deliberate way to commemorate the Stonewall uprising then it may have disappeared into history. But instead it entered the public consciousness. and it gave everyone in the gay and lesbian community something to build upon.

Suddenly there was a lot more visibility. Playwright Tennessee Williams rose to popularity and Truman Capote began to appear on mainstream TV. Gay people started to see themselves reflected in society. It would take much longer for trans people to feel the same however.

Gay people were now able to get licences to open bars and they even had windows onto the street so people could see in. It may not seem much now, but t the time it was a revelation.

The legacy of the Stonewall riots can also be seen in the legal and political victories that the LGBTQ+ rights movement has achieved over the past few decades. The riots helped to galvanize support for LGBTQ+ rights and brought attention to issues such as police brutality, discrimination, and violence against queer people. This led to the passage of laws and policies that protect the rights of LGBTQ+ people, including the repeal of sodomy laws, the eventual legalisation of same-sex marriage, and the expansion of anti-discrimination protections.

However, despite these victories, the legacy of the Stonewall riots also reminds us that there is still much work to be done. LGBTQ+ people continue to face discrimination, harassment, and violence, both in the United States and around the world. The fight for equality is ongoing, and it is up to all of us to continue the work that was started at Stonewall and ensure that everyone is able to live their lives with dignity and respect.